- Antradienis, Gruodžio 16, 2025

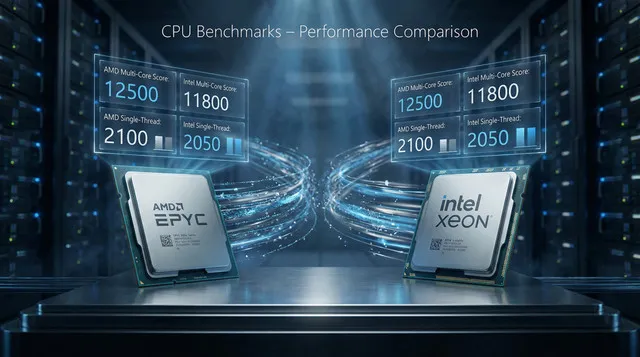

Choosing a server CPU often starts with comparing benchmark numbers – single-thread scores, multi-thread throughput, efficiency, etc. These benchmarks (e.g., PassMark, SPEC, Cinebench) are standardized tests that stress the CPU under synthetic workloads to provide quick performance metrics. For example, PassMark’s CPU Mark aggregates integer, floating-point, encryption and physics tests, and even includes a separate “single-thread” test to measure one‐core speed. In practice, buyers use these scores to rank CPUs and quickly narrow their choices. (For instance, PassMark reports that AMD’s 64‑core EPYC 9555P is significantly faster than Intel’s 64‑core Xeon 8592+ in both multi-thread and single-thread tests.)

Key Benchmark Metrics

-

Single-core performance: How fast a single CPU core runs (important for workloads that can’t fully parallelize). PassMark’s “Single Thread Rating” or SPEC’s single-thread scores are examples. A higher score means a faster clocked or more efficient core.

-

Multi-core performance: Aggregate throughput across all cores/threads. PassMark’s CPU Mark or SPECint-rate emphasizes total processing power. For example, PassMark shows the EPYC 9555P (64 cores) at around 135,000 vs 84,000 for the 64-core Xeon 8592+, and the EPYC 9355P (32 cores) at about 97,000. These scores give a rough ranking of raw compute capacity.

-

Power efficiency: Performance per watt. Data centers care about throughput per watt or per dollar. Benchmarks such as SPECpower or PassMark’s charts evaluate performance relative to TDP. For instance, the 32‑core EPYC 9355P has a 280W TDP versus 350W for the Xeon 8592+, meaning the AMD chip delivers higher PassMark scores with less power in that comparison. (Similarly, the 64‑core EPYC 9555P is a bit higher power (360W) than the Xeon (350W), but it also achieves much higher scores.)

In short, benchmarks yield headline numbers: single-thread score, multi-thread total score, and sometimes performance-per-watt or per-dollar. These metrics help you compare CPUs at a glance.

Check Bacloud dedicated server offers powered by AMD EPYC CPUs, delivering exceptional multi-core benchmarks, high efficiency, and enterprise-grade reliability for demanding workloads.

How Benchmarks Guide Server Choice

In practice, benchmark charts are used as a starting point. They quickly highlight which CPUs are generally faster. For example, PassMark data shows the new AMD EPYC chips not only outpacing older Intel models in raw scores but also matching or beating them in per-core performance. This might lead an engineer to favor EPYC for compute-heavy tasks. Data sheets and reviews will often quote single-core and multi-core scores (as well as features like cache size or supported memory) to guide procurement.

Even vendors use benchmarks in marketing. The IBM OpenPOWER and Intel Xeon lines often advertise SPEC CPU or SPECint results to show advantages. In addition, comparison sites incorporate price: for example, PassMark’s “CPU Value” metric divides the CPU Mark by list price or TDP, allowing buyers to consider performance per dollar or per watt. In short, benchmarks help narrow the field and highlight tradeoffs (e.g., higher raw speed vs higher power draw).

As a concrete example, consider the data:

-

Intel Xeon 8592+ – 64 cores/128 threads, 1.9 GHz base (3.9 GHz turbo), 350W TDP. PassMark CPU Mark ~84,013; Single-thread ~2,411.

-

AMD EPYC 9355P – 32 cores/64 threads, 3.55 GHz base (4.4 GHz turbo), 280W TDP. CPU Mark ~97,249; Single-thread ~3,742.

-

AMD EPYC 9555P – 64 cores/128 threads, 3.20 GHz base (4.4 GHz turbo), 360W TDP. CPU Mark ~135,441; Single-thread ~3,736.

These figures show that on paper, EPYC chips outperform Intel in both single-core and multi-core tests. In particular, both EPYCs have much higher single-thread scores (~3740 vs 2411) and far higher total scores. (The 9555P essentially doubles the thread count of the 9355P, yielding about a 40% higher aggregate score.) At the same time, the 9355P does this while drawing significantly less power, highlighting its better performance/watt.

These kinds of comparisons – “EPYC X has Y% higher score than Intel Z” – are precisely what benchmark charts deliver. They help IT teams determine which CPUs can meet the demands of CPU-bound workloads and fit within power/cooling budgets.

The Limits of Benchmarks

However, synthetic benchmarks have essential caveats. By design, they isolate the CPU or even a single aspect of it so that real workloads can behave quite differently. In general:

-

Synthetic vs. Real Workload: Benchmarks use fixed, repeatable tests (Cinebench, PassMark, SPEC, etc.) that stress particular CPU features. For example, Cinebench renders a 3D scene to max out the CPU, and PassMark runs math and crypto kernels. As one tech explainer notes, “synthetic benchmarks are controlled tests designed to stress specific hardware components or algorithms in isolation”. They are great for apples-to-apples comparisons, but they may not reflect actual usage. In contrast, real-world tests run full applications (video encoding, database queries, web server load, etc.), capturing unpredictable factors such as I/O waits and memory stalls. Often, a CPU may score high in a synthetic math test yet bottleneck elsewhere in practice. As the same article warns, “synthetic benchmarks offer precision and consistency but may not reflect real usage… For example, a storage drive might score high on a synthetic sequential read/write test but struggle with random access patterns common in database workloads”. The analogy applies to CPUs: a chip that wins on a pure-compute benchmark might not deliver proportional gains in an application if other subsystems (cache, memory, I/O) dominate.

-

Workload Variability: Real applications differ wildly. A CPU-bound scientific simulation will scale well with more cores and higher clocks (and synthetic scores will be predictive), but a web server or database might be limited by network, disk I/O, or software bottlenecks. In some cases, adding cores beyond a point yields diminishing returns (Amdahl’s Law), so a CPU with a higher single-thread score might actually do better. Benchmarks usually assume full-core utilization; many server tasks do not thoroughly saturate every thread. For instance, if your workload is lightly threaded or serial, the EPYC’s 32 or 64 cores won’t all contribute, and the higher single-core MHz of another CPU might matter more. Conversely, massively parallel jobs will more closely follow the multi-thread scores.

-

System-level Factors: Importantly, CPU benchmarks only test the processor. A real server’s performance also depends on memory, storage, networking, and software. A CPU can compute fast, but if the memory bus is slow or the disk is a bottleneck, overall throughput suffers. Benchmarks like SPECworkstation or full-system TPC tests exist for this reason – SPECworkstation 3, for example, includes dozens of workloads exercising CPU, I/O and memory bandwidth. This shows that full-system tests often include data transfers and graphics, not just CPU math. In your own workloads, factors such as disk I/O and RAM latency may be the actual limits. Thus, a higher CPU benchmark score may not translate to proportionally higher application performance if the rest of the system cannot keep up.

-

Configuration and Tuning: Benchmarks are usually run under ideal, controlled conditions. Actual servers run various software and virtualization layers and may have different BIOS or power settings. These can cause performance to deviate from benchmark claims.

-

Specific Feature Use: Finally, benchmarks may emphasize particular instructions or operations. For example, some tests might use AVX512-heavy code that benefits Intel’s architecture, while others use AES encryption, favoring AMD’s accelerators. Your workload might use neither. Likewise, a chip’s large L3 cache or fast memory controller might not get fully utilized in a synthetic test but could be critical for your database.

In summary, benchmarks are a simplified model. They are most useful for roughly gauging which CPU is generally faster or more efficient, but they cannot capture every detail of real-world use.

Where Can You Check CPU Benchmarks?

Once you understand why CPU benchmarks matter, the next practical question is where to check them. One of the most widely used and trusted resources is CPUbenchmark.net.

CPUbenchmark.net, operated by PassMark Software, is one of the most popular public databases for CPU performance comparison. It aggregates benchmark results from thousands of real-world test submissions and presents them in a clear, comparable format.

On this website, you can:

-

Compare single-thread performance, which is important for applications that rely on fast per-core speed (databases, some web workloads, legacy software).

-

Review multi-thread (CPU Mark) scores, valid for highly parallel workloads such as virtualization, containers, data processing, and rendering.

-

Check performance-per-watt and value metrics to evaluate efficiency and operational costs.

-

Compare server CPUs directly, including modern processors such as AMD EPYC 9355P, EPYC 9555P, and Intel Xeon models.

-

Filter CPUs by core count, clock speed, TDP, and release generation to narrow down the right server CPU for your needs.

For many users, CPUbenchmark.net is the first stop when determining which server CPU fits their workload. It provides a fast, vendor-neutral way to understand relative CPU performance before diving deeper into workload-specific testing or vendor benchmarks.

Takeaway: Benchmarks as a Guide, Not Gospel

Benchmarks make a helpful starting point in selecting a server CPU. They can quickly identify the leading contenders (as we saw, EPYC 9555P tops in raw PassMark scores while EPYC 9355P offers excellent throughput per watt). But they should be combined with workload-specific evaluation. Whenever possible, profile your actual application (or a close proxy) on candidate CPUs. Consider factors such as memory speed, I/O architecture, and the software stack. Remember that a CPU with a 50% higher benchmark score won’t always give a 50% boost in your service, especially if your bottleneck lies elsewhere.

Key recommendations: Use benchmark charts to narrow choices and compare relative strengths (cores, threads, clocks, TDP). But also validate with real workload tests and consider the whole system (memory, storage, network). Ultimately, a CPU is just one piece of the puzzle. Benchmarks provide valuable clues, but the best decision balances those clues with practical considerations of your specific server tasks.